In my freshman J-Term, I joined Dr. Quashnock's gravitational wave research group, wanting to learn about more fundamental physics and try my hand at work that was closer to computation and theory. I am still an active member of the group after nearly three years now, which makes it the group I have been a part of for the longest time. The group's focus has shifted in the field of gravitational wave physics each year, which has provided me with a wide range of knowledge on gravitational wave physics. While the group has mostly worked on analyses of the LIGO-Virgo-Kagra's publicly available gravitational wave events, we have also engaged in more theoretical projects during my time with the group. In addition to the wide scope of the field of gravitational wave physics I have developed after working with this group, I have learned lots of technical skills such as Python and more advanced mathematics. Working with the group, I have helped develop original simulations of gravitational wave emission, demonstrate the dependence these signals have on overtones, create an algorithm for predicting the astrophysical distance of an observed event, and have conducted a variety of analyses on the collaboration's publicly-available data. I will now describe my most influential year with this group in more detail.

An older picture of some members of the Carthage gravitational waves group (2022)

An updated picture of some of the members of the group (2024)

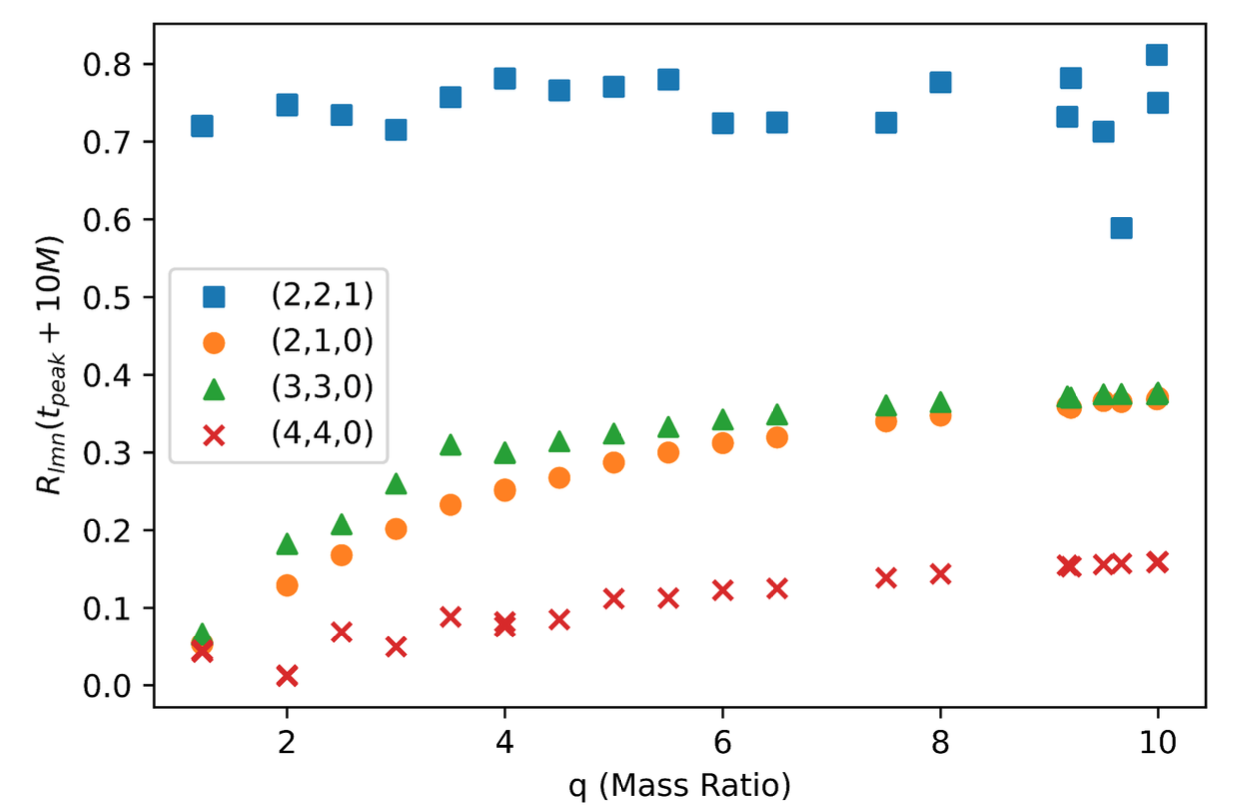

In my sophomore year, the group's focus shifted to a more theoretical project to do with the phase of gravitational wave emission following the merging of black holes, called the ringdown. As we began to learn early into the fall semester, there is a load of interesting physics to be learned from this phase, but because it is not nearly as energetic as the actual merging of black holes, so we have not yet detected any confident signals from this regime. Due to the lack of experimental data from this regime, researchers of this field turn to theorizing what the signals in it should look like, much like what was done prior to the discovery of the first gravitational wave, and model what these signals should look like. I personally spent a few months reading papers and watching talks on this subject of modeling and understanding the later phase of gravitational wave emissions, called black hole spectroscopy. During this time, I was beginning to recognize authors of papers and speakers whose work I had read in the previous year and begin to learn about the large groups on the subject. Most importantly, I also began to learn the history of gravitational wave physics, which I found very interesting to think about how historical factors had and continue to influence the trajectory of the field. This is an aspect of research that I continue to think about and that I try implementing into my more technical talks, especially when presenting to the public. I believe that giving this historical context can help in explaining science in addition to the intellectual stimulation. I had the opportunity to give three public talks on gravitational waves during my junior summer at Penn State, and from the feedback I received from them, my focus on historical context led to a very approachable and interesting talk.

As the fall semester began to end, the group began thinking of possible questions to ask and attempt to answer within the field of black hole perturbation theory. Given that the field is without any confident experimental data and relies heavily on theory and computation, starting from nothing and developing our own simulations to model the ringdown phase would not be realistic. In our literature review, we found a recent thesis written in the field by Iara Ota, who was later a post-doc in the same lab that I worked with during my sophomore summer at LSU. In this work, she provided links to her GitHub which contained the simulation data and code that generated some of the results of her thesis. We then spent around a month or two working through her code and eventually applied it to some new data collected from a previous simulation made by Dr. Emanuele Berti to confirm that the fundamental overtone in the ringdown was dominant and was comparable in amplitude to the first overtone. This was my most influential year working with the group, as it exposed me to the theoretical and computational aspect of gravitational wave research. I enjoyed the process of working on currently undetected physics which could provide a window into new physics when this phenomenon is experimentally detected.

Demonstrating the dependence the ringdown phase of gravitational wave emission has on the select overtones.

My sum of experience working with Dr. Quashnock's gravitational wave research group has been particularly influential in my development in using Python and in exposing to a relatively young field with promising opportunities. As our current detectors become more sensitive and the next generation of detectors come online, using gravitational waves to probe the fundamental nature of gravity and our early universe, both of which are fundamental questions that interest me the most and are what I'd like to pursue in graduate school, will become an increasingly important tool. Given their importance and their potential, I have learned through working with Dr. Quashnock's group that I would like to at least stay close to gravitational waves in grad school, if not directly working on some theoretical or computational problem in gravitational wave physics.